index.md 8.8 KB

Adding Interactivity

So far, we've learned how to describe the structure and properties of our user interfaces. Unfortunately, they're static and quite a bit uninteresting. In this chapter, we're going to learn how to add interactivity through events, state, and tasks.

Primer on interactivity

Before we get too deep into the mechanics of interactivity, we should first understand how Dioxus exactly chooses to handle user interaction and updates to your app.

What is state?

Every app you'll ever build has some sort of information that needs to be rendered to the screen. Dioxus is responsible for translating your desired user interface to what is rendered to the screen. You are responsible for providing the content.

The dynamic data in your user interface is called State.

When you first launch your app with dioxus::web::launch_with_props you'll be providing the initial state. You need to declare the initial state before starting the app.

fn main() {

// declare our initial state

let props = PostProps {

id: Uuid::new_v4(),

score: 10,

comment_count: 0,

post_time: std::time::Instant::now(),

url: String::from("dioxuslabs.com"),

title: String::from("Hello, world"),

original_poster: String::from("dioxus")

};

// start the render loop

dioxus::desktop::launch_with_props(Post, props);

}

When Dioxus renders your app, it will pass an immutable reference to PostProps into your Post component. Here, you can pass the state down into children.

fn App(cx: Scope<PostProps>) -> Element {

cx.render(rsx!{

Title { title: &cx.props.title }

Score { score: &cx.props.score }

// etc

})

}

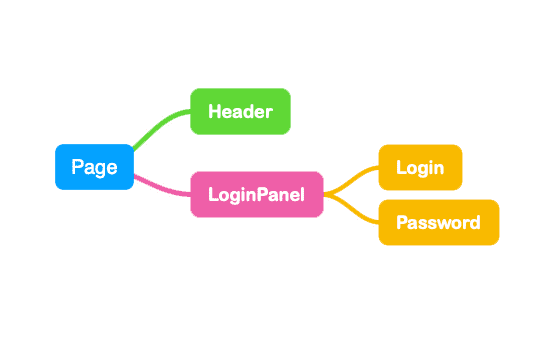

State in Dioxus follows a pattern called "one-way-data-flow." As your components create new components as their children, your app's structure will eventually grow into a tree where state gets passed down from the root component into "leaves" of the tree.

You've probably seen the tree of UI components represented using an directed-acyclic-graph:

With Dioxus, your state will always flow down from parent components into child components.

How do I change my app's state?

We've talked about the data flow of state, but we haven't yet talked about how to change that state dynamically. Dioxus provides a variety of ways to change the state of your app while it's running.

For starters, we could use the update_root_props method on the VirtualDom to provide an entirely new root state of your App. However, for most applications, you probably don't want to regenerate your entire app just to update some text or a flag.

Instead, you'll want to store state internally in your components and let that flow down the tree. To store state in your components, you'll use something called a hook. Hooks are special functions that reserve a slot of state in your component's memory and provide some functionality to update that state.

The most common hook you'll use for storing state is use_state. use_state provides a slot for some data that allows you to read and update the value without accidentally mutating it.

fn App(cx: Scope)-> Element {

let (post, set_post) = use_state(&cx, || {

PostData {

id: Uuid::new_v4(),

score: 10,

comment_count: 0,

post_time: std::time::Instant::now(),

url: String::from("dioxuslabs.com"),

title: String::from("Hello, world"),

original_poster: String::from("dioxus")

}

});

cx.render(rsx!{

Title { title: &post.title }

Score { score: &post.score }

// etc

})

}

Whenever we have a new post that we want to render, we can call set_post and provide a new value:

set_post(PostData {

id: Uuid::new_v4(),

score: 20,

comment_count: 0,

post_time: std::time::Instant::now(),

url: String::from("google.com"),

title: String::from("goodbye, world"),

original_poster: String::from("google")

})

We'll dive deeper into how exactly these hooks work later.

When do I update my state?

There are a few different approaches to choosing when to update your state. You can update your state in response to user-triggered events or asynchronously in some background task.

Updating state in listeners

When responding to user-triggered events, we'll want to "listen" for an event on some element in our component.

For example, let's say we provide a button to generate a new post. Whenever the user clicks the button, they get a new post. To achieve this functionality, we'll want to attach a function to the on_click method of button. Whenever the button is clicked, our function will run, and we'll get new Post data to work with.

fn App(cx: Scope)-> Element {

let (post, set_post) = use_state(&cx, || PostData::new());

cx.render(rsx!{

button {

on_click: move |_| set_post(PostData::random())

"Generate a random post"

}

Post { props: &post }

})

}

We'll dive much deeper into event listeners later.

Updating state asynchronously

We can also update our state outside of event listeners with futures and coroutines.

Futuresare Rust's version of promises that can execute asynchronous work by an efficient polling system. We can submit new futures to Dioxus either throughpush_futurewhich returns aTaskIdor withspawn.Coroutinesare asynchronous blocks of our component that have the ability to cleanly interact with values, hooks, and other data in the component.

Since coroutines and Futures stick around between renders, the data in them must be valid for the 'static lifetime. We must explicitly declare which values our task will rely on to avoid the stale props problem common in React.

We can use tasks in our components to build a tiny stopwatch that ticks every second.

Note: The

use_futurehook will start our coroutine immediately. Theuse_coroutinehook provides more flexibility over starting and stopping futures on the fly.

fn App(cx: Scope)-> Element {

let (elapsed, set_elapsed) = use_state(&cx, || 0);

use_future(&cx, || {

to_owned![set_elapsed]; // explicitly capture this hook for use in async

async move {

loop {

TimeoutFuture::from_ms(1000).await;

set_elapsed.modify(|i| i + 1)

}

}

});

rsx!(cx, div { "Current stopwatch time: {sec_elapsed}" })

}

Using asynchronous code can be difficult! This is just scratching the surface of what's possible. We have an entire chapter on using async properly in your Dioxus Apps. We have an entire section dedicated to using async properly later in this book.

How do I tell Dioxus that my state changed?

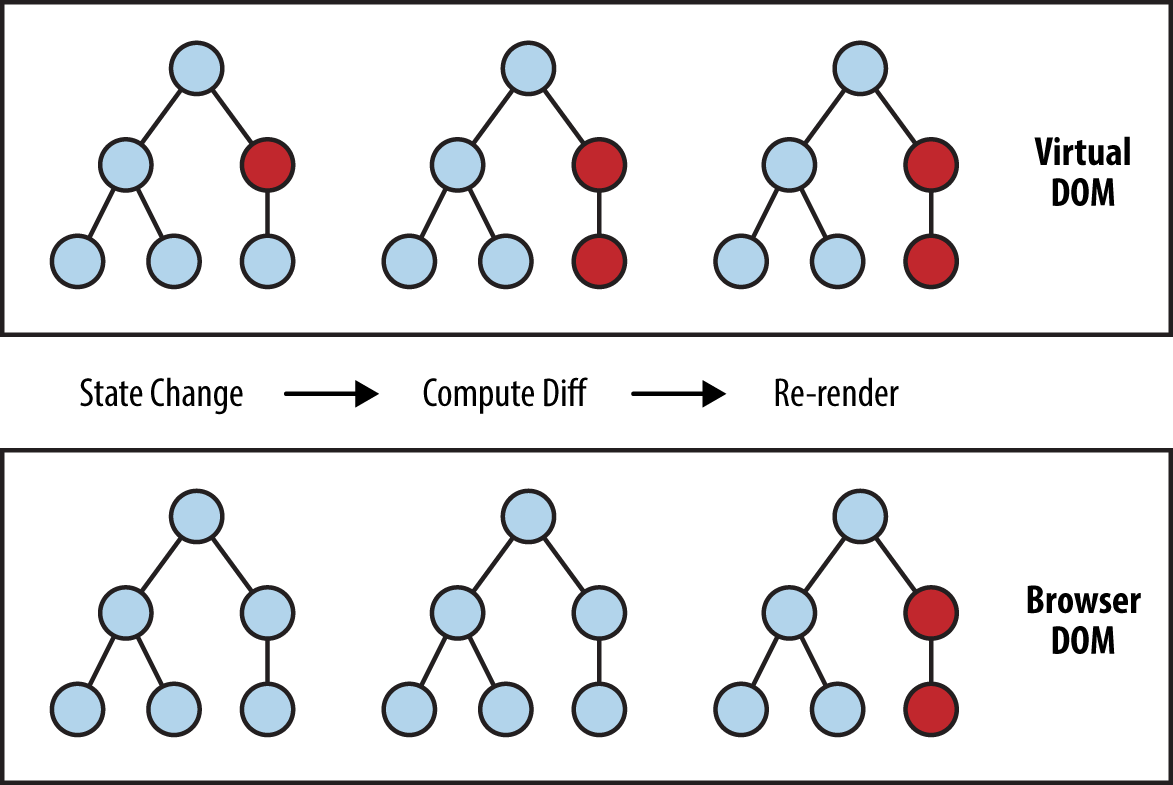

Whenever you inform Dioxus that the component needs to be updated, it will "render" your component again, storing the previous and current Elements in memory. Dioxus will automatically figure out the differences between the old and the new and generate a list of edits that the renderer needs to apply to change what's on the screen. This process is called "diffing":

In React, the specifics of when a component gets re-rendered is somewhat blurry. With Dioxus, any component can mark itself as "dirty" through a method on Context: needs_update. In addition, any component can mark any other component as dirty provided it knows the other component's ID with needs_update_any.

With these building blocks, we can craft new hooks similar to use_state that let us easily tell Dioxus that new information is ready to be sent to the screen.

How do I update my state efficiently?

In general, Dioxus should be plenty fast for most use cases. However, there are some rules you should consider following to ensure your apps are quick.

- 1) Don't call set—state while rendering. This will cause Dioxus to unnecessarily re-check the component for updates or enter an infinite loop.

- 2) Break your state apart into smaller sections. Hooks are explicitly designed to "unshackle" your state from the typical model-view-controller paradigm, making it easy to reuse useful bits of code with a single function.

- 3) Move local state down. Dioxus will need to re-check child components of your app if the root component is constantly being updated. You'll get best results if rapidly-changing state does not cause major re-renders.

Don't worry - Dioxus is fast. But, if your app needs extreme performance, then take a look at the Performance Tuning in the Advanced Guides book.

Moving On

This overview was a lot of information - but it doesn't tell you everything!

In the next sections we'll go over:

use_statein depthuse_refand other hooks- Handling user input